Interview w/ Mike Corrao

11:11: Gut Text is your second novel and the only thing it has in common with Man, Oh Man is that it’s not your typical novel. Before we jump into the text, I want to begin with the background of the book. What were your influences while crafting Gut Text?

MC: I was reading A Thousand Plateaus by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari [A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (French: Mille plateaux)] at the time. I love how incomprehensible it is. It’s cultural theory written with the desire to be more than just informative. The first paragraph of the book talks about how it’s radical that the authors chose to write the book under their own names. A lot of very bizarre terms pop up that are really interesting to latch onto. Like the “body without organs”. This is mainly supposed to be about the fluidity of the body, but sounds incredibly gory out of context. So, I think most of my work involves taking these things out of context and using them in ways that they definitely weren’t intended to be used. What else was I reading? I think it might have been Lonely Men Club—the Mike Kleine book—which has this very simplistic and straightforward sentence structure. Like, I owe this much money to Blockbuster or the sky is this color or I pray to this god. There’s just this mass of data that I find so engaging. As if I’m being provided with every bit of possible information.

11:11: The imagery in your books are… vivid. Where did that come from?

MC: It kind of comes from everywhere. I feel like all of the imagery is this collage of fake memories and misremembered phrases. Mutated versions of things I’ve encountered and then misremembered when they resurfaced.

11:11: There are so many references in this book. Was it your intention for people to pick up on them?

MC: Not necessarily. They’re there if you notice them, and they’ll of course add something, but I don’t want them to limit the experience of the reader. You can understand this book without having read the same books or watched the same movies as me.

11:11: So, it’s not cryptography…

MC: No. It’s just another potential layer for the reader to encounter. There’s the potential to be like oh he’s talking about BwO [Body without Organs] or he’s referencing Wolf Man’s case or Bolaño’s “alley of larches” from Antwerp—you can see what sources I’m pulling from, but there’s not necessarily a need to. There’s no course list. Of course the book is still weird, but you just have to approach with the right mindset.

11:11: This reminds me of an interview you did where you called Man, Oh Man a fictional essay?

MC: I think I called it essayistic fiction? Or.. fiction written as if it was an essay? Theory fiction. Along those lines.

11:11: Right, because not only are you playing with format, but you are mashing writing forms. How would you describe Gut Text?

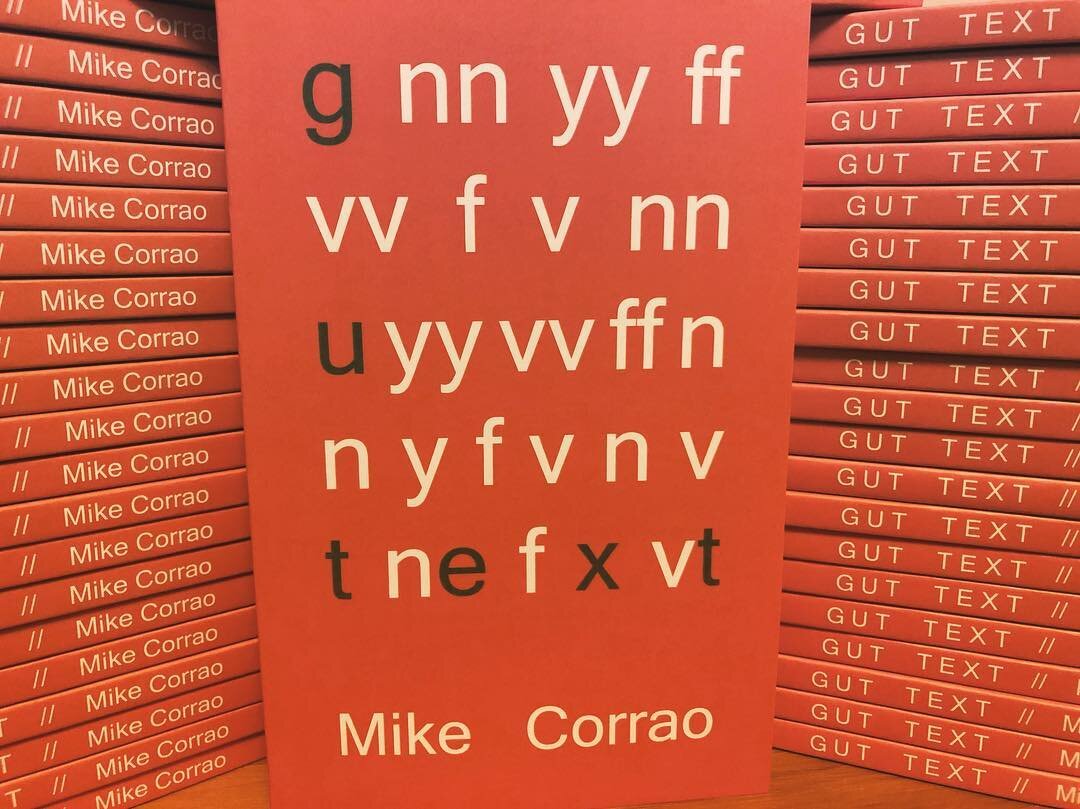

MC: I think it’s a similar boat to the last project. I don’t tend to work in a narrative space, so the progression is different. There tends to be this theoretical or ideological aspect pushing the book forward. I get bored so easily. It’s hard for me to latch onto plot—seeing a template laid out makes me lose my interest, it’s like filling out a form. So I think that’s what’s led me to these more unorthodox styles. Let’s say if Man, Oh Man is an essay about pseudo intellectualism, Gut Text is an essay about the ontology of the text, the state of the book as a physical object.

11:11: I think this book is a lot of fun, so you likewise keep your audience interested as well. On the back of the book, the first sentence is: you are holding a living organism.

MC: Yeah, I think books are often tasked with making you forget that you’re holding a physical object in your hands. Like you’re supposed to get lost in the diegesis and be more focused on what each character is doing. But I don’t want to do that. I want you to always be aware of the thing that you’re holding. You can’t escape the fact that each character is a part of the book. They are the set of pages on which they are written. I don’t want to move past the text’s status as an object.

11:11: You also have a physical dimension. You have breathing, expansion, the desire to disappear… They are three-dimensional.

MC: Because the text is the only thing (because there is no fabricated setting or these representations of people), you’re seeing everything that Gut Text contains. So, with ff, every facet of their consciousness is visible to you. It’s there. It’s on the page. And there’s nothing beyond that.

11:11: You said Gut Text is about the ontology of a book, it’s sounding like it is really about the phenomenology of a book.

MC: It’s object slouching towards subject. They all desire to transcend their role as text, but because they are limited by their medium, they can’t explore this other existence.

11:11: That’s fascinating. We have our limitations as humans. We want to go backwards and forwards in time, but to the text, we are gods. So when they want to be their best selves, they want to be an emanation of us.

MC: Yes, it was fun to think of this while writing the book. The character of Au is intended as this kind of stand in for the author (au short for author). And their speech often comes across as prophetic to the others simply because of the vast difference in their perspectives.

11:11: The text wants to be more, and that’s the heart of absurdism. This desire to be the thing that we idolize and the realization that we can’t. And yet, continuing. The characters want to be more and realize they can’t be more and we see it all.

MC: It was important to give these characters a mutated version of human desire. It’s not the desire to have this encounter with another body, but the desire to have a body in the first place. They strive for this biological status. To shift into another mode of existence. But with their limitations, this shift is very difficult, if not impossible. So their desires begin to change. nn wants to become nothing, yy wants to become large, etc. Realistically the book cannot become biological. I could write down ‘nn becomes a person’ but then the text stops being itself. It starts to show instead of act. It becomes representational rather than mimetic.

11:11: This isn’t a typical novel. It doesn’t follow the Joseph Campbell story arch of the Hero’s Journey and that’s one of the reasons we like it so much, which is also why we started 11:11 Press, because so many books are just telling the same story over and over and over and we think the world needs new stories. But new stories are hard to classify and the group of writers you’re lumped together with doesn’t have a name. It’s the Inside the Castle group, notable John Trefry and Mike Kleine and the online lit zines that are publishing this type of experimental writing: Occulum, X-R-A-Y… could you talk about this emerging community?

MC: Vi Khi Nao, Shane Jesse Christmass, Candice Wuehle, German Sierra, Elytron Frass. Minor Literature[s] and Always Crashing. They all have a very unique counter to the typical commercial book. And I can’t speak for any of them, but the way that I’ve been approaching my work has had a very anti-capitalist intent. Narrative arcs are reminiscent of the puritan work ethic, this idea that you find success or satisfaction through labor and accomplishment. That kind of economic climbing, pulling up by your bootstraps. Whereas a lot these recent experimental projects are more liken to Karl Schoonover’s idea of the wastrel. This figure meandering through the landscape with no progress or achievement. It’s often associated with slow cinema, but I think it works here as well.

11:11: It seems as though you view resolution as decadence.

MC: I love that word. I’ve been slipping it into everyday conversation. Referring to shit as decadent. I love it. But yes. I don’t want endings. I want movement, but not from point A to point B, just movement within a space. If that makes sense. I kind of talked about this recently in a review of mine I wrote about John Trefry’s new novel, Apparitions of the Living, where I talk about the labor of that book. It’s not the labor of progression, but of constructing the imagery of a scene. It’s a book that knows that words aren’t inherently present on the page. They must be written, they must be constructed. And I think that’s been a big part of this experimental thing, too, is knowing that the stuff on the page doesn’t just exist, you have to build the book yourself.

11:11: What I thought was interesting about your review was that you chose to write it in these segments. Kind of like how the book was written.

MC: Yeah (laughs). That was kind of self-indulgent on my part. I repurposed some of the vocabulary he used (bricabrac, cataplasm, mien, etc.) and used it in the review to talk about the qualities of the book. There was a good tweet I saw, I can’t remember who posted it, but it went along the lines of: if you don’t think your reviews are your art, then you’re doing a bad job. So I’ve tried to treat these reviews as another part of my bibliography. I don’t want them to be these dispassionate attempts at networking or whatever bullshit. I want them to be equally as important as my fiction / poetry.

11:11: Reviews are complicated, there’s a lot of politics behind the politics...

MC: I’m always ambivalent about bad reviews as a concept--at least in the small press community. Like if the work is problematic, if it’s racist, homophobic, transphobic, that’s a reason. That’s valid. But if it’s just a matter of me thinking your prose is shit, then why bother? I’ve only been writing reviews for books that I enjoy. My philosophy has been to request review copies for books that work in an unconventional space and say something that I think is interesting. Maybe the right way to put it is that I approach these reviews as more ekphrastic and critical. I’m going to talk about facets of the text that did something unconventional or that have an interesting ideology tied to them--i.e. certain representations of duration or urban modernity or whatever else.

11:11: You can definitely see these values in your work. It’s not often that abstract is made accessible. What’s more, in the process of doing this you didn’t alienate too many people - a difficult task within the genre.

MC: Thank you. The jump from Man, Oh Man! is so unexpected. You don’t pick up Gut Text after reading Man, Oh Man! and think, ahh yes, this is what I expected to come next. So, I’m happy the reaction isn’t: Mike’s gone crazy; but instead: this is a solid project that was put together purposefully.